Later this year – on 31 October, to be precise – a boy will be born in a rural village in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. His parents will not know it, but his birth will prove to be a considerable landmark for our species as his arrival will mark the moment when the human population reaches 7 billion.

There is no way of knowing for sure, of course, the identity of this baby boy. But demographers say that this date, place and gender are the most likely. India has the largest number of births each year – 27 million, roughly one in five of all global births – and Uttar Pradesh, India's most populous state with nearly 200 million citizens, would be the sixth most-populated country in the world if it were a nation. The majority of the state's births occur in the rural areas and the natural sex ratio at birth favours boys by a narrow margin.

We do not need a guiding star to direct us to the symbolism of this boy's birth: the world has known about this approaching milestone for many years. After all, it is only 12 years since the six billion mark was reached. And just 100 years ago, the human population stood at 1.6 billion. The urgent search for solutions to population growth has been a hot topic ever since the Rev Thomas Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798, stating that the "power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man". Every generation since has seen a prophet predicting doom for our species if we don't curtail our numbers. And yet the rise in headcount has continued inexorably and exponentially.

But with rising greenhouse gas emissions and resource depletion ever-growing concerns, the approach of this year's population landmark has become an awkward, even unwelcome presence in the environmental debate. No one likes to talk about it, for there are no easy answers. Even a mention of it can see the questioner accused of racism, colonialism or misanthropy. Increasingly, environmental thinkers such as Jared Diamond, George Monbiot and Fred Pearce have made the case that population growth is not, in fact, the real problem (the UN predicts that growth will plateau at nine billion around mid-century before slowly starting to fall), rather that a rapid rise in consumption is our most pressing environmental issue. There are more than enough resources to feed the world, they say, even in 2050 when numbers peak – a point made this week by a report jointly published by France's national agricultural and development research agencies. The problem is that we see huge inequities in consumption whereby, for example, the average American has the same carbon footprint as 250 Ethiopians. The French report concluded bluntly that "the rich must stop consuming so much".

Stood shoulder to shoulder, the entire human population could fit within the city limits of Los Angeles. We've got more than enough land upon which to collectively sustain ourselves, we just need to use it more wisely and fairly. But, given the stubborn realities of global inequalities, the question remains: are there too many of us to achieve a sustainable future?

Another report published this week – by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers – provocatively posed just this question in its title: "One planet, too many people?" It concluded the answer was "no", but only if food output was vastly improved through biotechnology, mechanisation, food processing and irrigation. In essence, it said we need to innovate and think our way out of our "population explosion" using technology.

Reducing consumption

Paul Ehrlich, the Bing professor of population studies at Stanford University in California, has been a figurehead of this debate ever since his still highly controversial book The Population Bomb was published in 1968, when the human population stood at 3.5 billion. The book attracted international attention with its stark, Old Testament predictions about how devastating famines would ravage the human populace in the 1970s and 80s and how "all important animal life" in our seas would be made extinct by over-fishing and pollution. Growth must be stopped, he urged, "by compulsion if voluntary methods fail". In 1971, he famously said he would take "even money" on the UK not existing as a state in the year 2000, adding that if it did survive it would be an impoverished island containing 70 million people. Asked about his prediction in 2000, he admitted he would have lost the bet, but added: "If you look closely at England, what can I tell you? They're having all kinds of problems, just like everybody else."

Ehrlich still stands by many of his predictions, but says that the timings were postponed by innovations that he never anticipated. For example, the so-called "green revolution" in agriculture enabled a much more productive global grain harvest than he ever imagined. Could technological innovations facilitate our continued expansion?

"We're already way past the carrying capacity of this planet by a very simple standard," he says. "We are not living on the interest from our natural capital – we are living on the capital itself. The working parts of our life support system are going down the drain at thousands of times the rate that has been the norm over the past millions and millions of years."

You cannot view consumption and population growth as separate issues, says Ehrlich: "In one sense, it is the consumption that damages our life support system as opposed to the actual number of people expanding. But both multiply together."

Reducing consumption is a much easier task, though, than tackling population growth, he says: "What many of my colleagues share with me is the view that we would like to see a gradual decline in population, but a rapid decline in consumption habits. We utterly transformed our consumption habits and patterns of economy in the US between 1941 and 1945, and then back again. If you've got the right incentives, you can change patterns of consumption very rapidly."

So, if you accept the planet is over populated – a big "if" for many observers – what are the solutions? "We have two huge advantages when trying to tackle population growth compared with consumption levels. First, we know what to do about it. If you educate women about their means to control reproduction, the odds are you will see a decline in fertility rates. Second, everyone understands the problem: you can't keep growing the number of people on a finite planet.

"But many economists still want people to consume more to get our economy back, but this will just see more resources destroyed. We also don't have what I'd call 'consumption condoms'. One of my colleagues once joked that the government ought to send round a truck to your home the day after you've been on a spending spree and offer to take everything you've bought back to the store. It would be the equivalent of a consumption morning-after pill."

The seven billion figure is eye-catching, but behind it lies a complicated demographic reality. For example, population growth in developed nations has largely stagnated. Even in places traditionally associated with rapid population growth, such as Bangladesh, birth rates have fallen considerably over the last generation, yet remain well above the natural replenishment rate of just above two children per woman. The only place where birth rates still remain at pre-industrial-age rates – six or more children per woman – is sub-Saharan Africa.

Every region requires its own solution, says Ehrlich. "In the US, where the population has risen by 10% in a decade, largely due to immigration, it is super critical that we tackle the population rise because we are super consumers. But, in general, in the rich countries where population growth has stopped or fallen, we should now be concentrating on reducing per capita consumption levels."

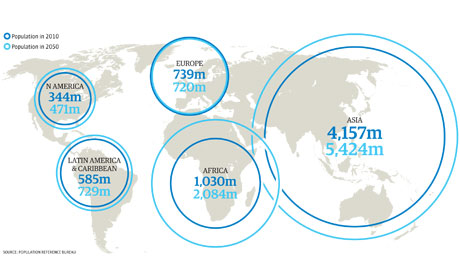

Projected population growth to 2050

Projected population growth to 2050

Ehrlich says that he is far more pessimistic now than he was when he wrote The Population Bomb. Increased immigration is an inevitability caused by increasing population and it will, he says, "become an ever-increasing political nightmare".

He also laments the lost opportunities: "The only thing we have done which was beneficial – but possibly fatal in the long run – was the 'green revolution'. But technological rabbits pulled out of the hat often have very nasty droppings. Frankly, I don't think most people are even remotely aware of what needs to be done to make our world a pleasant place to live in by, say, 2050."

James Lovelock, the independent scientist who first proposed the Gaia theory, is another prominent environmental thinker who has prescribed a bleak future for the human species if it continues to grow without restriction. He now advises people to "enjoy it while you can" because the outlook for future generations is, he believes, so stark.

"We do keep expecting a crash, as Malthus said, but then technology steps in, or something else, and alters the whole game," he says. "But it has its limit: it doesn't go to infinity. I expect we'll muddle through for the next 50 years, but sooner or later it will catch up with us."

Lovelock believes nations such as the UK now resemble a lifeboat: "In the UK, our population is growing slightly. It's containable. We do grow quite a bit of our food, so we should be OK, provided our climate doesn't change drastically. We could drop our calorie intake without noticing it in health terms. In fact, we'd improve our health like we did in the second world war.

"But I think we should call a halt to all immigration, or encourage people to go abroad. The average American has about 10 times as much land as we do. We're one of the most densely populated places in the world. In some respects, England is one large city. If you want to keep stuffing people in, you'll have to pay the price. I see us as a lifeboat with the person in charge saying: 'We can't take any more, or else we'll all sink.' America, meanwhile, could handle lots more immigration. Not politically, perhaps, but in terms of shared resources and land."

Optimism in Istanbul

Rotating spotlights illuminate the heavy rain clouds above a former coal-fired power station in the heart of Istanbul. Inside, a DJ ups the pace of the music as new arrivals browse the finger buffet. Business cards are being swapped as a speaker calls for hush. A promotional video begins to play.

The Silahtaraga Power Station – now an energy museum on the campus at Istanbul Bilgi University – could be the venue for a product launch anywhere in the world. But the crowd of business leaders, media and government officials has gathered for the launch of a report called Future Agenda: The World in 2020. Commissioned by Vodafone, Future Agenda claims to be the world's largest "open foresight project": an exercise in future-gazing involving 2,000 global participants, including the British Council, Google, Shell, PepsiCo and academics, with the aim of "analysing the crucial themes of the next 10 years".

But, in contrast to the pessimism offered by Lovelock and Ehrlich, there is a sense of pragmatism, even optimism, about both the opportunities and challenges a rising population will bring. And it's no accident that Istanbul has been chosen as the launch city. As continental Europe's only "megacity" – a population greater than 10 million – Istanbul believes itself to be an international beacon of how a city can grow both successfully and rapidly. The Economist has reported that Istanbul, with income growth of 5.5% and employment growth of 7.3% over the last year, is currently the world's "best-performing" city (although credit rating agencies question its status as a borrower).

Dr Tim Jones, the British author of Future Agenda, believes that by 2050, 75% of us will be living in cities. "The major trend we need to grasp is rural-urban migration," he says. "To put it simply, people are largely in the wrong place at the moment. They want to move where they perceive there to be opportunities. This means large cities. Immigration is a difficult political subject at the moment all over the world, but I believe migration will ultimately come to be seen in a positive light as the realisation is finally made that immigrants are a necessity to maintain ageing populations."

Our greatest challenge, says Jones, is to build cities that address the realities of rapid growth: "Sprawl is already being rejected as a deeply inefficient model for growing cities. Hong Kong and Paris are good examples where densities are key to success. They are seen as successful cities. For example, just 5% of Hong Kong's personal income is spent on transportation whereas in Houston it is 20% because everyone drives such huge distances commuting. Paris, with its six- and seven-storey housing, open spaces and street-based cafe culture is a model to aspire to. The Japanese are also role models when it comes to living densities. We must aspire to be like them. For example, we can't let China shoot past Japan and attempt to live like the Americans."

The gap between the world's rich and poor will worsen, he says, but that doesn't mean they will be forced apart geographically. "Residents within the world's megacities are already realising that they are all interdependent. In Mumbai, the rich want the inner-city slums to remain because they want the cheap labour close by. Equally, when slum dwellers have been given land on the outskirts of the city to tempt them away from the inner-city slums, many people have sold the land and moved back to the slum areas because they are closer to the work."

When it comes to consumption levels, Jones says there are already clear innovations emerging that will help to ease this problem. "The need and desire to actually own something is likely to reduce with rental of goods becoming more and more popular. We're already seeing this in cities with car [sharing] schemes such as Zipcar."

The rise of the city will also have a huge impact on geopolitics, predicts Jones, with some megacities wielding far more power than many nation states. "Already we are seeing that the C40 [a group of large cities committed to tackling climate change] is having more impact than the G20. I see far more political action being enacted by city mayors in the future."

Çaglar Keyder, a professor of sociology at Istanbul's Bogaziçi University, agrees that the citizens of Istanbul are very proud of their city's rise, but growth has not come without some problems: "There has been rapid urban regeneration; knocking down shanties and putting people in high rises. Retired, older people are moving further out and the young are moving in, but birth rates are falling. Traffic and environmental pollution is where the growth is most felt."

Standard of living

Carl Haub has been counting the world's people for the last three decades. The Conrad Taeuber chair of population information at the Population Reference Bureau in Washington DC and author of the World Population Data Sheet, an internationally respected annual report that provides population, health and environmental indicators for more than 200 countries, he has near-total recall of the myriad figures that underpin 2011's seven-billion landmark.

"In terms of future growth, everything depends on the birth rates in developing nations," he says. "There is a presumption that the global average will come down to less than two children per woman after 2050, but there are big question marks about this. For example, everyone is pessimistic about sub-Saharan Africa where birth rates overall are not coming down at all. The political situation is key. Both Zimbabwe and Cote d'Ivoire were seen as bright spots by demographers, but now things are much bleaker. Sub-Saharan Africa will double in size by 2050. Nigeria is 158 million now, but will be 326 million by 2050 and will continue rising. Starvation is actually quite rare at the moment in sub-Saharan Africa, but standards of living will continue to fall. And without Aids, there would be 200-300 million more people in Africa by 2050. Many people in the west just don't understand what the standard of living is like in these countries. Some of the consequences are invisible to us in the west, but for how long?"

Migration and ageing are two key, interconnected issues, argues Haub. "China has now got a serious problem with ageing," he says. "I predict they will relax their one-child policy within five years. In Japan, where ageing is a huge problem, they are now having a major nursing crisis with very few young women wanting to be nurses. They're having to import them from Vietnam and the Philippines."

City living does help to suppress birth rates, says Haub. This can clearly be seen in Bangladesh, he says, where rural-to-city migration is driven by desperation. Once in the city, the need to have lots of children to work the land disappears, they become expensive to support and access to family planning is readily available.

But migration inevitably brings with it political tensions. "Terrorism is the curve ball in the immigration debate. Turks and Slavs were tolerated in Germany for a long period, but not now. The chancellor Angela Merkel recently said that assimilation is not working. The birth rate in Germany is very low – about 1.4 children per woman, which is close to demographic suicide – and immigration has maintained the population. In cities such as Frankfurt, where there is a very sizeable Turkish population, there is now a fear of radicalism amid isolated communities. And then there is religion, of course. But, in general, I see this as a decreasing influence when it comes to family planning. In Africa, for example, cultural norms have a much greater impact. Here we see issues such as polygamy and men boasting about how many children they have."

So are there any signs of optimism?

"We have to be realistic," he says. "We are just not going to see fewer people on the planet in the near future. But there are some developing countries where the birth rate is under control. Thailand is seen as the No 1 developing country when it comes to family planning. The birth rate there is 1.8. Indonesia also has a very efficient family-planning system.

"But how far do you go? South Korea has a birth rate of 1.2 and in Taiwan it is 1.0. It is the lowest in the world and means the country is literally dying. If you do want a reduced birth rate, then well organised family planning campaigns are much more important than economic growth. It might be unfashionable to say so, but international aid acts as a catalyst for this. Monetary assistance is key at the beginning to get these campaigns going."

Haub is already thinking ahead to the eighth billion person being born sometime around 2025. "The 20th century saw many things happen that greatly helped to reduce the death rate, such as public-health campaigns, immunisation and provision of clean water. The challenge for the 21st century is different: it's all about managing birth rates."

• Future Agenda paid Leo Hickman's travel expenses to attend its event in Istanbul.

Comments

14 January 2011 8:42AM

Maybe I'm being naive, but I trust Mother Nature to decimate our species numbers, when it becomes necessary.

(Wherever I put the apostrophe, it looks wrong - sorry)

14 January 2011 9:02AM

species'

14 January 2011 9:14AM

On the topic of feeding the world's population you might be interested to read WorldWatch Institute's new publication 'State of the World 2011: Innovations that nourish the planet'. Big launch in Washington DC yesterday.

From that site:

With Worldwatch Institute's focus on sustainability I expect they come to some different conclusions to the Institute of Mechanical Engineers.

14 January 2011 9:37AM

Any writer still supporting Erlich's failed ravings should be regarded with extreme suspicion - as populations achieve standards of living far above mere subsistence, the trend is for that population's breeding to fall below replacement. The obvious answer is to ensure everyone on the planet has access to affordable energy and thus raise the standards of living above subsistence for all populations.

14 January 2011 9:52AM

kiwiinlondon@9:37

Unfortunately the method that produces unlimited amounts of affordable energy does not appear to have been discovered yet.

14 January 2011 10:01AM

The idea of England being some kind of "island" that might escape the problems of a future global food failure are extremely dangerous as they imply that a country could escape a global problem. This is also happening with climate change where the fact that it will be far off lands such as Mali who are/will suffer most encourages some policy-makers to continue believing it´s not such a big deal. There will be no "islands" of developed lifestyles if this problem gets too big. 1,000,000,000 people are already estimated to be in different states of "hunger" and growing numbers of impoverished people are the worst thing that can happen to the remaining areas of crucial global ecosystems such as the tropical rainforests. The tropical forests apart from all their plant and animal wealth and their role in the global climate are also vitally important in the absorption of CO2 and the production of oxygen - might be a bit suffocating on those future islands.

14 January 2011 10:19AM

"rural-urban migration"....yea gods, I'm glad I'll be dead by then.

14 January 2011 10:19AM

Each person's environmental footprint has grown (2006 data) to a mean of 2.6 global hectares (gha) per person, yet the total biological capacity of the planet would allow only about 1.8 gha per person (www.footprintnetwork.org).

The United Nations' Global Environment Outlook-4 report reveals a scale of unprecedented ecological damage, with close to 2 billion likely to suffer absolute water scarcity by 2025.

The Living Planet Report of WWF calculates that humankind will need 200% of the planet’s total biocapacity (forestry, fisheries, croplands) by 2050.

Go figure.

14 January 2011 10:19AM

Leo, you talk about technology solutions and available landmass being able to provide for a global popn of 9bn, but don't you think that accommodation of of all 9bn will in effect encourage even more growth?

14 January 2011 10:20AM

Technology is most defiantly not the answer. We have to live within the planets carrying capacity, technology may allow us to make more with what we have but the principle stands.

We have two options either humans instigate a decline in our population humanely, or nature will instigate the decline. And nature won't be so kind.

We have already seen the beginning of natures response in the floods and bush fires, record food prices both almost certainly a result of global warming and over consuption. Its gonna get much much worse.

14 January 2011 10:21AM

Nature will restore balance at some point.

Being as we are a little smarter than your average animal we can avoid the population to food collapse for longer than they can, as we have science to increase yields.

But as can already be seen greed by speculators is driving food prices to what the UN calls dangerous levels and rioting and civil unrest is starting to break out.

Add in that, unless kiwiinlondon knows where that cheap plentiful energy source is, energy prices are also being manipulated solely for profit and under heavy demand from India and Chine, something will have to give.

Very likely we will continue to breed at a rate that manages to increase the global population whilst millions die of disease, hunger and poverty in a totally miserable and mostly short existence that they would better off not being born in an ongoing cycle. Although obviously that won't be any who speculates on food or energy.

Better we controlled our numbers than condemn so many people to a living death, but we can always sit and wring our hands as it happens instead of doing anything.

14 January 2011 10:22AM

David Attenborough (a patron of the Optimum Population Trust )says:

“I’ve seen wildlife under mounting human pressure all over the world and it’s not just from human economy or technology - behind every threat is the frightening explosion in human numbers.

“I’ve never seen a problem that wouldn’t be easier to solve with fewer people, or harder, and ultimately impossible, with more. That’s why I support the OPT, and I wish the environmental NGOs would follow their lead, and spell out this central problem loud and clear.”

I think he should know, as he gets about a bit.

14 January 2011 10:24AM

We, we, we, we, we...

what WE really mean is the minute minority who are using up way beyond their fair share of resources to live lives that are unnecessarily luxurious.

Unless 5 bathrooms, 3 cars, motorbikes, jetski's, jets, multiple homes, rooms full of clothes, plasma screens and tech devices everywhere etc etc are actually necessary for a normal human life..

14 January 2011 10:30AM

Mother Nature will start to take a grip on the situation, by mass flooding of lowland countries.

14 January 2011 10:40AM

Ehrlick also famously made a bet with Julain Simon, author of The Ultimate Resource. Ehrlick said for any 10 minerals or resources, the price in 10 years time would be higher than it currently is now. Simon, arguing that innnovation and the economic incentive to find alternatives would mean prices would be lower.

Guess who won?

Simon. And Ehrlick padyed him a thousand dollars, but refused to continue the bet for another 10 year period as Simon wanted for double or nothing....

14 January 2011 10:41AM

The green revolution is based on the availability of ammonium phosphate fertilizer (amongst others). Ammonium phosphate fertilizer is based on the availability of ammonia via the Haber process. Ammonia is based on the availability of Methane for its hydrogen content.

If we run out of methane, no Methane leads to no Ammonia, leads to no Ammonium phospgate Fertilizer leads to no food.

Of course there are other sources of Hydrogen for the Haber Process such as electrolysis of sea water, but cast amounts of energy are required. With the green movement consistently opposing nuclear power, where is this energy going to come from.Also, we can start by stopping burning methane.

14 January 2011 10:42AM

Blame the pope.

14 January 2011 10:46AM

Population is a very complex issue as @LeoHickman's article makes clear. It is the one issue where we need to keep stepping back and looking at the big picture. If you just concentrate on the detail it is very easy to come up with conclusions and ideas that are clearly very mistaken when you look at the big picture.

Yes the world's very large and growing human population puts an incredible strain on the environment and with a much lower human population there would be much less impact on the environment. That much is very clear.

However, this often leads people to the mistaken conclusion that an effective means to address our impact on the environment is to address the human population with measures to prevent growth or even reduce. This superficially looks like a worthwhile idea until you properly evaluate what this would actually mean in practice, and what these measures would actually achieve in a given timescale. Even if it were possible to produce an immediate and drastic reduction in the birth rate by mutual consent this would have only a limited effect on slowing down population growth and will not result in any short or even medium reduction in the population. This is simply because human beings are capable of living a very long time, and medical advances mean an increasing part of the population are living much longer.

Let us be very clear about this though, there is no way of immediately reducing the birth rate by mutual consent. The message of having less children has been put out for a very long time with virtually no effect. The evidence clearly shows that the birth rate is connected to economic conditions, culture etc, and not what people are asked to do.

There are 2 factors which effect populations from the ecological point of view (the science of ecology deals with population dynamics), these are recruitment and mortality. Human population growth and level is due to the influence of both these factors. Medical advances mean that motality from common illnesses have been greatly reduced and people in general live much longer. Likewise far less children die in infancy. So birth rate itself is not so much the controlling factor - the basis of this growth is factually very clear - far more of those born survive into old age. Antibiotics probably represent the single biggest advance in medicine. Common bacterial infections that used to commonly prove fatal, are now minor things. Although antibiotic resistance of some bacteria has slightly reversed this - but not enough to make any significant overall effect.

This means we have 2 contrary factors at work. First we are asking people to have less children, whilst beavering away at medical research, which will result in far more of the population living into old age, and living longer. These clearly are mutually contradictory objectives. However, deliberately limiting our medical technology so more people die, when these deaths are preventable, is clearly immoral, and no doubt it would be applied unevenly, and unjustly i.e. the poor would die, and the rich would still get the medical treatment. Likewise any attempt to limit the birth rate by coercion would mean the use of authoritarian measures - despotism. Power is applied unevenly in despotic regimes, some are favoured, others oppressed - it is a despicable and unjust means of government. Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Just look at the MPs expenses scandal to see how even in democracies like our own, those in power are incapable of judgement that does not favour themselves and their friends/family. More authoritarian regimes are even more corrupt.

Likewise war to reduce the human population, or god forbid euthanasia or genocide are even more despicable and immoral. There is therefore no means to seriously effect the human population from an environmental impact point of view in the short to medium term without resorting to immoral measures that will result in great suffering and injustice. Yes you can produce ideas, but these are science fiction and they will not work in the real world, they have been repeatedly attempted, and they have failed.

Yes we can and must address the population issue. But morally this can only take place if we completely change our society through peaceful means. It cannot take place in our current competitive hothouse economy and political situation. We must develop a society based on cooperation and not competition. This is possible because it is the natural means of human interaction, and the competitive aspect is something imposed on our society only since the first civilizations arose. It is not natural, and it is not inevitable, it was a system of design to suit a powerful ruling elite.

There may be typos I have not had time to properly proof read or edit my comment, it was typed in fast.

14 January 2011 10:48AM

People who think population is a problem are generally saying those in the third world shouldn't breed. That is a completely racist argument. If the first world consumed less and more sustainably we could fit many more on this planet but no that will damage our lifestyles so thats apparently not an option. Also educated people tend to have less children so how about instead of just saying we have to stop birth rates in the third world we help to fund stable countries that provide opportunity. The birth rate would decline then. But no thats apparently "socialism" to help others.

14 January 2011 10:49AM

@kiwiinlondon:

There's the rub. We are running out of fossil fuels and other minerals. It is largely because of the use of fossil fuels that we have been able to dodge Malthus for so long.

14 January 2011 10:54AM

In addition, to my above comments. The 2 most useless concepts that do the most violence to rational thought are blame and justification. In other words it is all someone else's fault, or someone's own particular actions or point of view are somehow justified. These are legalistic concepts to aid the often arbitrary decisions of actual legal systems. However, these otherwise useless concepts stop us from seeing things clearly. They are a means of avoiding uncomfortable facts we find inconvenient and they produce false logic. People can avoid looking at uncomfortable facts and therefore come to false conclusions. They also mean that people refuse to look at the consequences of their own actions by justification. These stupid concepts produce highly egocentric thinking. Nowhere is this clearer than with regard to the human population issue.

14 January 2011 10:57AM

High Population is caused by POVERTY.

There are numerous studies showing that the poorer people are the more children they have - this is because they cannot afford contraceptives, and in the 2nd and 3rd worlds there is no social security nor pension system for older adults. Parents have children in the 3rd world so that they can work.

In the West, where salaries are high (on a world standard), people do not starve every day, and there is health care and government pensions, the birth rates have dropped precipitously - only last week in the Guardian there was a re-hash of an article about Japan's population problem, where no-one is having children - in every Western country barring the US. And it is only increasing in the US because of the poor Latinos who are emigrating there.

If the West stopped taking an unfair share of the wealth, then there would be less population.

Consumption is also a western ideal brought about by the idea of "infinite growth" of the economy - this was never going to be possible in the long term and it is a failing idea now. The UK economy will not be able to carry on growing by 3% every year for ever ... it would eventually have consumed all the world's economic resources - let alone the rest of the world consuming.

This innate idea of capitalism is going to have to be changed, in favour of management and sustainable living.

I would also point out that only this week in the New Scientist there were articles about how the world could feed 7 billion people if it legislated on banks and investors who buy vast amounts of food and then sell it on at higher prices.

Speculation for the purposes of greed is causing misery around the world as we speak in both food and oil prices.

14 January 2011 10:57AM

This is absolutely right and to provide some figures to highlight the issue:

If population was to increase to 9bn at current consumption per capita and with most the population growth in Asia, CO2 output would increase by 20%.

If you stopped all population growth today but allowed the whole world to consume at the same level as the USA, CO2 output would increase by around 600%

14 January 2011 10:58AM

The difficulty with Ehlich,s idea the "we" should reduce "our "consumption levels is that it would entail the haves in our society reducing their use of resources more than the have nots who ,by definition, are using less .

He is surely not naive enough to think that those with power money and influence would voluntarily take a large reduction in their standard of living.

I can think of no precedent in history for this the World War 2 experience was surely irrelevant since it was obvious that this was temporary.

14 January 2011 10:59AM

Rapa Nui

14 January 2011 11:01AM

Too many people and poor food distribution plus greedy speculation are the problems facing us now.

They will pale in comparison to the nightmare of water shortages. Then the shit will hit the fan unless we can tap into the oceans. But at what cost?

If speculators sink their greedy teeth into the supply of water there will be war as millions are displaced in the search for fresh water supplies.

We should get rid of speculation for a start. Next, improve the distribution of food and the long term availability of water on a global scale. Easy to write but I see no other way for the ongoing survival of mankind - if that's the will of the planet.

14 January 2011 11:01AM

kiwiinlondon, you are not reading very closely, the predictions are all coming true he was just wrong about timing, we are indeed living on the capital itself and not the interest like any sensible person would. It cannot last and I see no alternative other than to scale back our greedy lifestyles, and that will only buy the human race time.

Maybe someone will discover fusion power so we can actually have electric cars, that only leaves us the problem of what we are going to eat and what all our "stuff" is going to be made of.

14 January 2011 11:01AM

Michael Portillo and Anne Widdicombe should do a sex ed DVD featuring constant, graphic and intense coital demonstrations between the 2. This would be compulsory education for everyone in the world and should be shown daily on all major channels until the world's population can only associate sex with utter horror and stop rutting for a whole generation.

14 January 2011 11:05AM

ABSOLUTE POPPYCOCK.

CURRENTLY,ALL THE WORLD'S POPULATION CAN BE HOUSED IN A STATE,OR PLOT OF LAND THE SIZE OF TEXAS.

DO NOT BELIEVE SUCH CLAPTRAP FEAR-MONGERING BY THE SOCIAL ENGINEERS.

POPULATION REDUCTION IS THE REAL AGENDA HERE FOLKS.

14 January 2011 11:07AM

I agree that the human population will ultimately be controlled by external factors ie rising sea levels, restricted food production etc, but why must people talk about Mother Earth as if she's some sentient being, an ethereal old biddy with leaves in her hair who will strike us all down with tsunamis and earthquakes...

It's just a bit of rock wot we happen to live on. Get a grip.

14 January 2011 11:07AM

Well done Leo. A good article that must have taken alot of research to write. Good to see this very important subject being raised.

14 January 2011 11:08AM

I think that people don't want to face the truth about population growth. The fact is that people have to be more responsible for their own reproduction. Just because you can have six children, does it mean you should? Insisting upon having as many children as you want as a right is ridiculous. It's my right to smear chocolate all over my living room walls but that doesn't mean it's a great idea. In the future, people will have to take more responsibility for the numbers of children they produce. Another uncomfortable fact is that often people who have the largest families rely on the state to feed them. Ordinary people who don't rely on benefits simply don't have huge families because they know they can't afford them. It's controversial - but I think that having any more than four kids is nonsensical. We have birth control now. There are no such thing as 'accidents'. A woman can easily stop getting pregnant and I say that as a woman myself. It's time everyone grew up.

14 January 2011 11:08AM

National Geographic are covering this issue in every edition in 2011.

Peter Sinclair has posted a link to their video clip about this.

The key word is balance. Balance in the supply of resources, but unfortunately a line has been crossed a while ago where the carrying capacity of the planet cannot profit for this need.

Obviously the first target must be the biggest consumers. The debt they own is so great I doubt whether they realise the impossible scale of the problem.

Ultimately I feel that tradegy is all but unavoidable and this affects me deeply.

14 January 2011 11:12AM

Absolutely. Every measure should be put into place to get the world population down to 3 billion again over time. This can go from taxes to education to publicity to many others, and if that doesn't work, then to law, like China. The alternatives are only the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. Knowing man and his past record on planning ahead, we'll probably have to resort to the cavalry again.

14 January 2011 11:15AM

If we took Tony Blair, David Cameron and David Beckham to the vets, it might show we were serious about reducing the population.

14 January 2011 11:20AM

What nonsense to claim a shortage of food will lead to the end of the human race

If the worst comes to the worst, famine will decimate the population until a balance between supply and demand is arrived at

Thats the way it has worked for many millions of years for most of the worlds species

14 January 2011 11:20AM

This article fails to tackle the real problem. Since I was a lad, I've been running away from cement. I've seen it gobble up leafy towns, parks, landscapes, seashores, you name it. I keep having to move out to the margins, until the cement catches up and I have to move again. Keep that world population popping and soon there won't be anywhere to move to, as the cement dots peppering the planet connect and merge into one large, continuous car park. A sad, dead end for the only green planet that we can see as far as our telescopes reach. So sad. How long will we turn a deaf ear to our demise as humans?

14 January 2011 11:21AM

No need for lengthy,expensive reports consuming ever more of our valuable ,diminishing planetary resources - just plain old fashioned coitus interruptus.

14 January 2011 11:22AM

The Dutch don't deserve that! Also I'm not sure low level flooding would actually achieve any drop unless such land was overwhelmed by Tsunami events. People will just move unless you were thinking about cultivated land being permanently flooded so reducing food production and "shortening" fresh water supplies in which case yep it would make difference.

14 January 2011 11:22AM

Excellent article, Leo.

The interesting thing about the population debate is how little we can actually do about it. The most extreme example of population control is in China with its one-child policy. Yet demographers comparing population growth to other culturally similar countries think that the net loss of population was minimal - most Asian societies have very rapidly dropping family size once a certain minimal level of wealth is reached. The 'problem' is specific to certain countries and regions such as Africa and the Middle East. The problem elsewhere is over consumption.

The reality is that we will never be able to pursuade the majority of people to give up their dreams of a big house and car and three foreign holidays a year. They can either be forced to drop those dreams (i.e. by economic collapse), or we can break the link between 'wealth' and resource consumption. I would love to see a society where everyone grew their own food in allotments and cycled everywhere and wore lots of clothes instead of having central heating. But (except at the margins), its not going to happen, we've constructed our societies physically the wrong way.

The only way out is technology. But technology doesn't have to mean rampant use of biotech and giant nuclear reactors. It can mean the application of better information tecnology to reduce soil erosion and water use in agriculture. To create giant power grids that allow us to export Saharan solar power and North Sea wind power all over the developed world, and then converting our transport, manufacturing and heating systems to use this power. It means developing forms of nuclear power that don't leave future generations horrendous waste problems. It means using both science and politics to ensure we don't take more from the seas than can be sustained in the long term. It means dealing with migration in a way which is both humane and beneficial to the host nations.

It won't be easy, but quite simply, we have no choice.

14 January 2011 11:29AM

I'm not sure it's fair to blame the pope, since it appears that non-procreation is an important clause in his contract.

More pertinently, we could blame the people who like to accept a geriatric celibate as a relevant guide to their life-style decisions.

By the way, where is George Monbiot when we want to hear from him?

14 January 2011 11:30AM

It's not so much the figure of near 7 billion that disturbs me, but more so the distribution of the population. 4 billion alone in Asia is a worrying statistic, and one could claim that the immigration issue here in the UK could get a hell of a lot worse if you bear that stat in mind. I hope the Government take this into consideration, and act on it.

I believe that poverty, lack of education, and religion are prime causes of the current figure in Asia and Africa.

As for the points made about tragedy, Mother Nature etc, unfortunately this is hugely inevitable in the most densely populated areas, and the events of this week are merely the beginning...

14 January 2011 11:33AM

Two things:

The fact that "... environmental thinkers such as Jared Diamond, George Monbiot and Fred Pearce have made the case that population growth is not, in fact, the real problem ...", pretty much confirms that they are idiots. If consumption decreases faster than population increases, ultimately there will be a tipping point at which millions, no, billions die. No doubt Jared Diamond, George Monbiot and Fred Pearce will be on the panel deciding who should be slaughtered. Also, if we do go with "sustainable" agriculture, energy etc., the land required per person will increase, bringing the tipping point nearer.

You can analyse it as much as you want, but ultimately we, as a species must decide what our end game is - as many people as possible whatever the quality of life? - as many people as is sustainable in balance with our surroundings (whatever that means) - or just limit population by whatever means are necessary to a number - say 1 billion.

The Chinese are the only nation that have had the guts to recognise the problem and respond with the one child policy (yes I do know about the imbalance of boys and girls - but that is not the policy, that;s the culture). Its about time the rest of the world did the same.

14 January 2011 11:34AM

The Earth is currently underpopulated. The Earth can support 12 billion people. It cannot support 12 billion millionaires.

One real and valuable way to address overpopulation would be to encourage values like pride, self-worth, and spiritual conviction. This would inevitably lead some people to conclude that modern life, and in particular, their own individual lives, were not measuring up to their own minimums.

A philosophy where selfishness, and greed, are somehow 'good' leads people into ignorance. The instinct to blindly breed (for women) and blindly 'fit in' for men, meets with no check or balance from free will.

Our 'economic growth' and the 'success' of capitalism are like a firework in the night sky on the cosmic scale. Using this as a starting point, there is quite a lot 'we' can do about 'overpopulation'.

14 January 2011 11:34AM

This part hit me the most before reading any further:

"We've got more than enough land upon which to collectively sustain ourselves, we just need to use it more wisely and fairly."

It is the thought that it is just "us" on this planet, forgetting about all the other life that has a right to survive too without us encroaching upon them.

14 January 2011 11:35AM

Soylent Green is people!

14 January 2011 11:35AM

I think Doug Stanhope said it best. (NSFW, obviously)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YkgDhDa4HHo

14 January 2011 11:35AM

That's a lot of potential zombies. Gonna need more bullets and a bigger barricade when the zombie apocalypse arrives...

14 January 2011 11:36AM

As the West, with its high standard of living isn't growing, the solution is to raise the standard of living of the poorer countries until they too (as human nature has demonstrated) stabilise their populations. What they need is cheap power as KiwiInLondon said above.

The solution is not here yet, but I'd bet it will come from a Western, capitilist consuming country.

If we reduce the standard of living in the West then it seems likely that the Wests population will start to rise again.

14 January 2011 11:40AM

I think most nations recognised the problem. However, in my honest opinion, the only reason China responded with action was down to the simple fact that they are one of the chief contributors to the current figure.